Welcome back to part two of Getting to Know Tanzania Through Facts and Figures. This week we continue with facts and figures about the economy of Tanzania.

Despite it’s natural beauty, Tanzania is in the bottom 10% of the world’s economies. Tanzania’s GDP, in terms of purchasing power (what goods in Tanzania would cost in the USA), is a trivial $57.5 billion in comparison to the United States’ $14.26 trillion. (At the official exchange rate (Tanzania’s GDP converted to US dollars), Tanzania’s GDP is only $22.16 billion.) Per capita, this is $1,400 (201st*). Per capita GDP in the States is $46,000 (11th). The percentage of the population below the poverty line in Tanzania is 36%. There is nothing surprising about this figure. The percentage of the population below the poverty line in the United States is 12%. I find this rather astounding. How is it the country with the world’s largest and most powerful economy find itself with 36,865,454 people living in poverty? Tanzania only has 14,777,471 people living below the poverty line. The US has almost two and a half times the amount of people living in poverty that Tanzania does but over 600 times the GDP. Now it is worth considering what is meant by poverty line. This metaphorical line is based on many figures and varies considerably country-to-country. This means what qualifies as poverty in one country may not qualify in another. Thus is should be noted that poverty in the US is very different from poverty in Tanzania where poverty means living on a dollar a day.

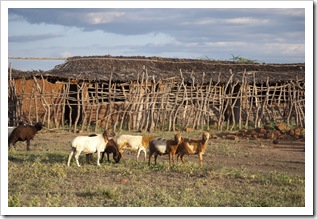

Tanzania’s economy is primarily agriculture, with 40% of the GDP comprised of agricultural activities. This is rather amazing given that only 4.23% of the land is arable. (18.01% of the United States is suitable for farming). Additionally, 80% of the labour force works in agriculture and 85% of exports are agricultural goods. Things grown for mass-market in Tanzania include: coffee, sisal, tea, cotton, cashew nuts, tobacco, cloves, corn, wheat, cassava, and bananas. Tanzania exports $2.744 billion in gold, coffee and cashew nuts, manufactured goods and cotton to mainly India, Japan, and China.

In terms of public debt, Tanzania owes 24.8% of it’s GDP. Externally, it owes $7.07 billion dollars. These figures are pennies compared to the debts of America. In public debt, the United States owes 52.9% of it’s GDP. This, of course, doesn’t include state and inter-governmental debt. If it did, add another 30% of the GDP. In external debt, the United States owes $13.45 trillion. That make us #1 in terms of debt. Congratulations us.

Tanzania consumes 32,000bbl/day of oil (112th), all of which is imported. The United States, as the number one consumer of oil, uses 19.5 million bbl/day, of which only 8.514 million bbl/day is produced internally. In 2008, Tanzania consumed 560.7 million cu m of natural gas (93rd) whereas the US consumed 657.2 billion cu m(1st). Given these figures, it should come as no surprise that the United States is the largest emitter of carbon dioxide on the planet. Congratulations again.

Tanzania has a striking number of cell phone lines: 14.723 million. This figure becomes clearer when you know that many Tanzanians have two or even three different phone lines with different companies. A more reasonable number is the 179,849 main lines Tanzania posses. For comparison, the US has 270 million cell phone lines and 150 million land lines.

Americans love their televisions. The fact that as of 2006, there were 2,218 different TV broadcasting stations proves this. Tanzania, on the other hand, has just 3. The US is also home to 231 million internet users while Tanzania has just 520,000 though this figure is rising.

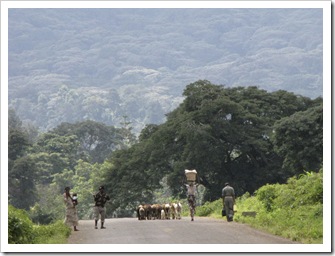

Ask any Tanzanian and one thing they’ll say about the country is the poor infrastructure. And indeed, it hasn’t quite the development as the United States. Of the 78,891 km of roads in Tanzania, 72,083 of them are unpaved. (The United States has more miles of roads than any other country coming in with 6,465,799 km.) Tanzania also has 125 airports,of which only 9 are paved. (Again the US has more airports than any other nation with 15,095.)

Another thing Tanzanians will say about their country is it’s history of non-violence. Tanzanians proud themselves on their passive nature. Tanzania spends only .2% of its GDP on military (170th of 173). The US throws 4.06% of its GDP ($578,956,000,000) to its military. Though the US rank appears lower, 28th world-wide, it is the highest among western nations and the countries ahead of it include: Oman, Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan, and Israel among others. (Iceland comes in last at 0.00%. I guess there isn’t a lot of desire for invading frozen islands in the middle of the North Atlantic.) Additionally, Tanzania has taken in more refugees than any other African nation (480,613) mostly from Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Comparatively the United States accepted 100,159 refugees from around the world in 2004-2005.

Though the USA may have better infrastructure and a longer life expectancy, this does not mean that it is a better place to live. The United States is shackled with debt and produces an outrageous amount of green house gases.

Hopefully these statistics help give you a better picture of Tanzania and where it stands in the world.

* Disassociated numbers in parenthesis indicate rank among the world

Note: All facts and figures compliments of the CIA World Factbook and the math is brought to you by my handy Casio calculator.